n-body problem

The  -body problem is the problem of predicting the motion of a group of celestial objects that interact with each other gravitationally. Solving this problem has been motivated by the need to understand the motion of the sun, planets and the visible stars. Its first complete mathematical formulation appeared in Isaac Newton's Principia (the

-body problem is the problem of predicting the motion of a group of celestial objects that interact with each other gravitationally. Solving this problem has been motivated by the need to understand the motion of the sun, planets and the visible stars. Its first complete mathematical formulation appeared in Isaac Newton's Principia (the  -body problem in general relativity is considerably more difficult). Since gravity was responsible for the motion of planets and stars, Newton had to express gravitational interactions in terms of differential equations. An important fact, which Newton proved in the Principia, is that celestial bodies can be modelled as point masses.

-body problem in general relativity is considerably more difficult). Since gravity was responsible for the motion of planets and stars, Newton had to express gravitational interactions in terms of differential equations. An important fact, which Newton proved in the Principia, is that celestial bodies can be modelled as point masses.

Informal version of the Newton n-body problem

The physical problem can be informally stated as:

- Given only the present positions and velocities of a group of celestial bodies, predict their motions for all future time and deduce them for all past time.

More precisely,

- Consider

point masses

point masses  , ... ,

, ... , in three-dimensional (physical) space. Suppose that the force of attraction experienced between each pair of particles is Newtonian. Then, if the initial positions in space and initial velocities are specified for every particle at some present instant

in three-dimensional (physical) space. Suppose that the force of attraction experienced between each pair of particles is Newtonian. Then, if the initial positions in space and initial velocities are specified for every particle at some present instant  , determine the position of each particle at every future (or past) moment of time.

, determine the position of each particle at every future (or past) moment of time.

In mathematical terms, this means to find a global solution of the initial value problem for the differential equations describing the  -body problem.

-body problem.

Mathematical formulation of the n-body problem

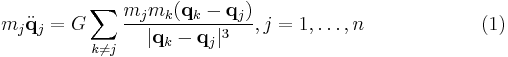

The general n-body problem of celestial mechanics is an initial-value problem for ordinary differential equations. Given initial values for the positions  and velocities

and velocities  of n particles (j = 1,...,n) with

of n particles (j = 1,...,n) with  for all mutually distinct j and k , find the solution of the second order system

for all mutually distinct j and k , find the solution of the second order system

where  are constants representing the masses of n point-masses,

are constants representing the masses of n point-masses,  are 3-dimensional vector functions of the time variable t, describing the positions of the point masses, and G is the gravitational constant. This equation is Newton's second law of motion; the left-hand side is the mass times acceleration for the jth particle, whereas the right-hand side is the sum of the forces on that particle. The forces are assumed here to be gravitational and given by Newton's law of universal gravitation; thus, they are proportional to the masses involved, and vary as the inverse square of the distance between the masses. The power in the denominator is three instead of two to balance the vector difference in the numerator, which is used to specify the direction of the force.

are 3-dimensional vector functions of the time variable t, describing the positions of the point masses, and G is the gravitational constant. This equation is Newton's second law of motion; the left-hand side is the mass times acceleration for the jth particle, whereas the right-hand side is the sum of the forces on that particle. The forces are assumed here to be gravitational and given by Newton's law of universal gravitation; thus, they are proportional to the masses involved, and vary as the inverse square of the distance between the masses. The power in the denominator is three instead of two to balance the vector difference in the numerator, which is used to specify the direction of the force.

For every solution of the problem, not only applying an isometry or a time shift, but (unlike in the case of friction) also a reversal of time gives also a solution.

For n = 2, the problem was completely solved by Johann Bernoulli (see Two-body problem below).

General considerations: solving the  -body problem

-body problem

In the physical literature about the  -body problem (

-body problem ( ≥ 3), sometimes reference is made to the impossibility of solving the

≥ 3), sometimes reference is made to the impossibility of solving the  -body problem. However care must be taken when discussing the 'impossibility' of a solution, as this refers only to the method of first integrals (compare the theorems by Abel and Galois about the impossibility of solving algebraic equations of degree five or higher by means of formulas only involving roots).

-body problem. However care must be taken when discussing the 'impossibility' of a solution, as this refers only to the method of first integrals (compare the theorems by Abel and Galois about the impossibility of solving algebraic equations of degree five or higher by means of formulas only involving roots).

The  -body problem contains 6

-body problem contains 6 variables, since each point particle is represented by three space (displacement) and three velocity components. First integrals (for ordinary differential equations) are functions that remain constant along any given solution of the system, the constant depending on the solution. In other words, integrals provide relations between the variables of the system, so each scalar integral would normally allow the reduction of the system's dimension by one unit. Of course, this reduction can take place only if the integral is an algebraic function not very complicated with respect to its variables. If the integral is transcendent the reduction cannot be performed.

variables, since each point particle is represented by three space (displacement) and three velocity components. First integrals (for ordinary differential equations) are functions that remain constant along any given solution of the system, the constant depending on the solution. In other words, integrals provide relations between the variables of the system, so each scalar integral would normally allow the reduction of the system's dimension by one unit. Of course, this reduction can take place only if the integral is an algebraic function not very complicated with respect to its variables. If the integral is transcendent the reduction cannot be performed.

The  -body problem has 10 independent algebraic integrals

-body problem has 10 independent algebraic integrals

- three for the center of mass

- three for the linear momentum

- three for the angular momentum

- one for the energy.

This allows the reduction of variables to 6 − 10. The question at that time was whether there exist other integrals besides these 10. The answer was given in 1887 by H. Bruns.

− 10. The question at that time was whether there exist other integrals besides these 10. The answer was given in 1887 by H. Bruns.

Theorem (First integrals of the  -body problem) The only linearly independent integrals of the

-body problem) The only linearly independent integrals of the  -body problem, which are algebraic with respect to

-body problem, which are algebraic with respect to  ,

,  and

and  are the 10 described above.

are the 10 described above.

(This theorem was later generalized by Poincaré). These results however do not imply that there does not exist a general solution of the  -body problem or that the perturbation series (Lindstedt series) diverges. Indeed Sundman provided such a solution by means of convergent series. (See Sundman's theorem for the 3-body problem).

-body problem or that the perturbation series (Lindstedt series) diverges. Indeed Sundman provided such a solution by means of convergent series. (See Sundman's theorem for the 3-body problem).

Numerical integration

N-body problems can be solved by numerically integrating up the differential equations of motion. Many different ways to do this to varying degrees of accuracy and speed exist.[1]

The simplest integrator is the Euler method, but this is only first order. A second order method is leapfrog integration, but higher-order integration methods such as the Runge–Kutta methods can be employed. Symplectic integrators are often used for n-body problems.

Numerical integration is O(N2), but tree structured algorithms can improve this to O(n log(n)).

Two-body problem

If the common center of mass of the two bodies is considered to be at rest, each body travels along a conic section which has a focus at the center of mass of the system (in the case of a hyperbola: the branch at the side of that focus). The two conics will be in the same plane. The type of conic (circle, ellipse, parabola or hyperbola) is determined by finding the sum of the combined kinetic energy of two bodies and the potential energy when the bodies are far apart. (This potential energy is always a negative value; energy of rotation of the bodies about their axes is not counted here).

- If the sum of the energies is negative, then they both trace out ellipses.

- If the sum of both energies is zero, then they both trace out parabolas. As the distance between the bodies tends to infinity, their relative speed tends to zero.

- If the sum of both energies is positive, then they both trace out hyperbolas. As the distance between the bodies tends to infinity, their relative speed tends to some positive number.

Note: The fact that a parabolic orbit has zero energy arises from the assumption that the gravitational potential energy goes to zero as the bodies get infinitely far apart. One could assign any value to the potential energy in the state of infinite separation. That state is assumed to have zero potential energy (i.e. 0 joules) by convention.

See also Kepler's first law of planetary motion.

Three-body problem

For n ≥ 3 very little is known about the n-body problem. The case n = 3 was most studied and for many results can be generalized to larger n. Many of the early attempts to understand the 3-body problem were quantitative, aiming at finding explicit solutions for special situations.

- In 1687 Isaac Newton published in the Principia the first steps taken in the definition and study of the problem of the movements of three bodies subject to their mutual gravitational attractions. His descriptions were verbal and geometrical, see especially Book 1, Proposition 66 and its corollaries (Newton, 1687 and 1999(transl.), see also Tisserand, 1894).

- In 1767 Euler found the collinear periodic orbits, in which three bodies of any masses move such that they oscillate along a rotation line.

- In 1772 Lagrange discovered some periodic solutions which lie at the vertices of a rotating equilateral triangle that shrinks and expands periodically. Those solutions led to the study of central configurations , for which

for some constant k>0 .

for some constant k>0 .

.gif)

Specific solutions to the three-body problem result in chaotic motion with no obvious sign of a repetitious path. A major study of the Earth-Moon-Sun system was undertaken by Charles-Eugène Delaunay, who published two volumes on the topic, each of 900 pages in length, in 1860 and 1867. Among many other accomplishments, the work already hints at chaos, and clearly demonstrates the problem of so-called "small denominators" in perturbation theory.

The restricted three-body problem assumes that the mass of one of the bodies is negligible; the circular restricted three-body problem is the special case in which two of the bodies are in circular orbits (approximated by the Sun-Earth-Moon system and many others). For a discussion of the case where the negligible body is a satellite of the body of lesser mass, see Hill sphere; for binary systems, see Roche lobe; for another stable system, see Lagrangian point.

The restricted problem (both circular and elliptical) was worked on extensively by many famous mathematicians and physicists, notably Lagrange in the 18th century and Poincaré at the end of the 19th century. Poincaré's work on the restricted three-body problem was the foundation of deterministic chaos theory. In the circular problem, there exist five equilibrium points. Three are collinear with the masses (in the rotating frame) and are unstable. The remaining two are located on the third vertex of both equilateral triangles of which the two bodies are the first and second vertices. This may be easier to visualize if one considers the more massive body (e.g., Sun) to be "stationary" in space, and the less massive body (e.g., Jupiter) to orbit around it, with the equilibrium points maintaining the 60 degree-spacing ahead of and behind the less massive body in its orbit (although in reality neither of the bodies is truly stationary; they both orbit the center of mass of the whole system). For sufficiently small mass ratio of the primaries, these triangular equilibrium points are stable, such that (nearly) massless particles will orbit about these points as they orbit around the larger primary (Sun). The five equilibrium points of the circular problem are known as the Lagrange points.

King Oscar II Prize about the solution for the n-body problem

The problem of finding the general solution of the n-body problem was considered very important and challenging. Indeed in the late 1800s King Oscar II of Sweden, advised by Gösta Mittag-Leffler, established a prize for anyone who could find the solution to the problem. The announcement was quite specific:

Given a system of arbitrarily many mass points that attract each according to Newton's law, under the assumption that no two points ever collide, try to find a representation of the coordinates of each point as a series in a variable that is some known function of time and for all of whose values the series converges uniformly.

In case the problem could not be solved, any other important contribution to classical mechanics would then be considered to be prize-worthy. The prize was finally awarded to Poincaré, even though he did not solve the original problem. (The first version of his contribution even contained a serious error; for details see the article by Diacu). The version finally printed contained many important ideas which led to the theory of chaos. The problem as stated originally was finally solved by Karl Fritiof Sundman for n=3.

Sundman's theorem for the 3-body problem

In 1912, the Finnish mathematician Karl Fritiof Sundman proved that there exists a series solution in powers of  for the 3-body problem. This series is convergent for all real t, except initial data which correspond to zero angular momentum. However these initial data are not generic since they have Lebesgue measure zero.

for the 3-body problem. This series is convergent for all real t, except initial data which correspond to zero angular momentum. However these initial data are not generic since they have Lebesgue measure zero.

An important issue in proving this result is the fact that the radius of convergence for this series is determined by the distance to the nearest singularity. Therefore it is necessary to study the possible singularities of the 3-body problems. As it will be briefly discussed in the next section, the only singularities in the 3-body problem are

- binary collisions

- triple collisions.

Now collisions, whether binary or triple (in fact of arbitrary order), are somehow improbable since it has been shown that they correspond to a set of initial data of measure zero. However there is no criterion known to be put on the initial state in order to avoid collisions for the corresponding solution. So Sundman's strategy consisted of the following steps:

- He first was able, using an appropriate change of variables, to continue analytically the solution beyond the binary collision, in a process known as regularization.

- He then proved that triple collisions only occur when the angular momentum c vanishes. By restricting the initial data to

he removed all real singularities from the transformed equations for the 3-body problem.

he removed all real singularities from the transformed equations for the 3-body problem. - The next step consisted in showing that if

then not only can there be no triple collision, but the system is strictly bounded away from a triple collision. This implies, by using the Cauchy existence theorem for differential equations, that there are no complex singularities in a strip (depending on the value of c) in the complex plane centered around the real axis.

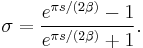

then not only can there be no triple collision, but the system is strictly bounded away from a triple collision. This implies, by using the Cauchy existence theorem for differential equations, that there are no complex singularities in a strip (depending on the value of c) in the complex plane centered around the real axis. - The last step is then to find a conformal transformation which maps this strip into the unit disc. For example if

(the new variable after the regularization) and if

(the new variable after the regularization) and if  then this map is given by

then this map is given by

This finishes the proof of Sundman's theorem. Unfortunately the corresponding convergent series converges very slowly. That is, getting the value to any useful precision requires so many terms that his solution is of little practical use.

The global solution of the n-body problem

In order to generalize Sundman's result for the case n>3 (or n=3 and c=0) one has to face two obstacles:

- As it has been shown by Siegel, that collisions which involve more than 2 bodies cannot be regularized analytically, hence Sundman's regularization cannot be generalized.

- The structure of singularities is more complicated in this case, other types of singularities may occur.

Finally Sundman's result was generalized to the case of n>3 bodies by Q. Wang in the 1990s. Since the structure of singularities is more complicated, Wang had to leave out completely the questions of singularities. The central point of his approach is to transform, in an appropriate manner, the equations to a new system, such that the interval of existence for the solutions of this new system is  .

.

Singularities of the n-body problem

There can be two types of singularities of the n-body problem:

- collisions of one, two or n particles, but for which q(t) remains finite.

- singularities in which a collapse does not occur, but q(t) does not remain finite. The latter ones are called no-collisions singularities. Their existence has been conjectured for n > 3 by Painlevé (see Painlevé's conjecture). Examples of this behavior have been constructed by Xia[2] and Gerver.

See also

- Many-body problem (quantum mechanics)

- Euler's three-body problem

- Virial theorem

- Few-body systems

- natural units

- N-body simulation

References

- Diacu, F.: The solution of the n-body Problem, The Mathematical Intelligencer,1996,18,p. 66–70

- Mittag-Leffler, G.: The n-body problem (Price Announcement), Acta Matematica, 1885/1886,7

- Saari, D.: A visit to the Newtonian n-body Problem via Elementary Complex Variables, American Mathematical Monthly, 1990, 89, 105–119

- Newton, I.: Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, London, 1687: also English translation of 3rd (1726) edition by I. Bernard Cohen and Anne Whitman (Berkeley, CA, 1999).

- Wang, Qiudong: The global solution of the n-body problem (Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy (ISSN 0923-2958), vol. 50, no. 1, 1991, p. 73–88., URI retrieved on 2007-05-05)

- Sundman, K. E.: Memoire sur le probleme de trois corps, Acta Mathematica 36 (1912): 105–179.

- Tisserand, F-F.: Mecanique Celeste, tome III (Paris, 1894), ch.III, at p. 27.

- Hagihara, Y: Celestial Mechanics. (Vol I and Vol II pt 1 and Vol II pt 2.) MIT Press, 1970.

- Boccaletti, D. and Pucacco, G.: Theory of Orbits (two volumes). Springer-Verlag, 1998.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Z. Xia, “The Existence of Noncollision Singularities in Newtonian Systems,” Annals Math. 135, 411-468, 1992

- Havel, Karel. N-Body Gravitational Problem: Unrestricted Solution (ISBN 978-09689120-5-8). Brampton: Grevyt Press, 2008. http://www.grevytpress.com

External links

- Three-Body Problem at Scholarpedia

- More detailed information on the three-body problem

- Regular Keplerian motions in classical many-body systems

- Applet demonstrating chaos in restricted three-body problem

- Applets demonstrating many different three-body motions

- On the integration of the n-body equations

- A java applet to simulate the 3-d movement of set of particles under gravitational interaction

- Javascript Simulation of our Solar System

- n-body simulation of many particles in JavaScript

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

True anomaly

True anomaly Semi-minor axis

Semi-minor axis

Eccentric anomaly

Eccentric anomaly Mean longitude

Mean longitude True longitude

True longitude